Flavors in the Frame: Where Kota Kinabalu’s Architecture Meets Its Street Food Soul

Kota Kinabalu isn’t just a gateway to tropical islands—it’s a sensory collision of flavors and facades. Wandering its streets, I was struck by how food and architecture tell the same story: one of layered history, cultural fusion, and vibrant local life. From colonial shophouses serving roti canai to modern markets glowing at dusk, every bite comes with a backdrop. The scent of sizzling satay drifts past weathered wooden columns; the clatter of woks echoes beneath tiled eaves. This is where taste and texture go beyond the plate, where the built environment becomes part of the meal. In Kota Kinabalu, you don’t just eat the culture—you walk through it.

First Impressions: Stepping into Kota Kinabalu’s Urban Tapestry

Arriving in Kota Kinabalu, the city unfolds like a watercolor painting washed with coastal light. The silhouette of Mount Kinabalu, often veiled in morning mist, anchors the skyline, while the South China Sea glimmers beside a palm-lined waterfront promenade. The city’s architecture tells a story before a single word is spoken—low-rise buildings with colonial-era facades stand beside sleek glass towers, and traditional Malay-style roofs peek out from behind modern signage. This visual mosaic reflects a history shaped by indigenous communities, Chinese traders, British administration, and post-independence growth. The Sabah State Legislative Building, perched on a peninsula, is a modern interpretation of traditional design, its grand domes and arched colonnades echoing motifs from Borneo’s cultural heritage. It stands not as a relic, but as a living symbol of identity, much like the city’s food—rooted in tradition, yet constantly evolving.

The waterfront area, a favorite among locals and visitors alike, offers a seamless blend of leisure and commerce. Wide pedestrian paths invite strollers, while shaded seating areas provide refuge from the tropical sun. Here, architecture serves function and feeling—open spaces allow sea breezes to flow freely, cooling the air naturally, while the layout encourages social interaction. Street vendors set up near benches and fountains, their carts strategically placed where foot traffic converges. This thoughtful design isn’t accidental; it reflects a deep understanding of how people move, gather, and engage with public spaces. As the sun sets, the promenade transforms. String lights flicker on, and the scent of grilled seafood fills the air. The transition from day to night reveals another layer of Kota Kinabalu’s rhythm—one where architecture and atmosphere conspire to elevate the simplest of meals into a moment of connection.

What makes Kota Kinabalu’s urban landscape particularly compelling is its accessibility. Unlike cities where historic districts are preserved behind velvet ropes, here, heritage is lived. You don’t observe the culture from a distance—you step into it. A century-old shophouse isn’t a museum exhibit; it’s where a grandmother flips roti canai on a hot griddle. A colonial-era market isn’t a tourist attraction; it’s where mothers buy fresh vegetables for dinner. This integration of past and present, of structure and sustenance, sets the stage for a culinary journey that is as much about place as it is about taste. The city’s architecture doesn’t just house its food culture—it shapes it, supports it, and celebrates it.

The Heritage Trail: Shophouses, Hawkers, and Hidden Eateries

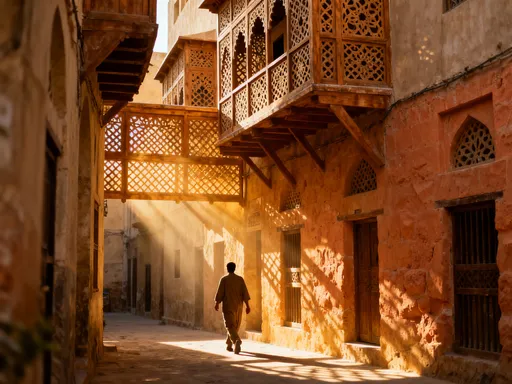

Walking through Gaya Street and the surrounding historic districts feels like stepping into a living archive. The pre-war shophouses, with their distinctive five-foot ways—covered walkways supported by slender columns—create a rhythm of light and shadow that guides the pedestrian. These buildings, often two or three stories high, were designed for the tropics: high ceilings promote airflow, wooden shutters allow for ventilation while offering privacy, and tiled roofs deflect the intense sun. Their facades, though weathered, retain intricate details—carved panels, pastel-colored stucco, and wrought-iron railings that hint at the craftsmanship of a bygone era. Today, these structures are not preserved in amber but repurposed with purpose. The ground floors, once home to family-run shops, now host food stalls that have served the same recipes for generations.

The connection between architecture and food is evident in the way these spaces function. The open frontage of each shophouse allows vendors to spill out onto the sidewalk, creating an inviting threshold between inside and outside. A stall selling kolo mee, a springy egg noodle dish topped with minced pork and char siu, operates beneath a faded awning, its owner moving effortlessly between kitchen and counter. The design of the space—narrow in depth but wide in frontage—maximizes visibility and accessibility. Customers don’t just eat here; they linger, chat, and become part of the street’s pulse. The airflow, channeled by the building’s layout, carries the aroma of garlic, soy sauce, and roasted meat, drawing in passersby like a siren’s call. These shophouses were never meant to be sealed off; they were built for interaction, for commerce, for life.

In the old market area, the link between structure and sustenance deepens. The wet market, housed in a low-slung building with corrugated metal roofing and concrete flooring, is a symphony of color and sound. Baskets of tropical fruits—mangosteens, rambutans, and pineapples—sit beside trays of fresh fish and hanging cuts of meat. But beyond the produce, it’s the cooked food section that reveals the true heart of the place. Here, women in aprons serve steaming plates of hinava, a Kadazan-Dusun dish of raw marinated fish, and bubur pedas, a spicy porridge layered with roots and herbs. The kitchen setups are simple—gas stoves, woks, and stainless steel counters—but they are perfectly adapted to the environment. The high ceilings allow heat to rise, while strategically placed fans keep the air moving. The building’s design, though utilitarian, is a quiet hero, enabling vendors to work efficiently and customers to eat comfortably despite the humidity.

Cultural Crossroads: How Architecture Shapes Food Communities

Kota Kinabalu’s multicultural identity is not just reflected in its population but embedded in its built environment. Each ethnic community has left its mark on the city’s architecture, and in turn, those structures influence how food is prepared, shared, and celebrated. In the Chinese quarters, temples with curved roofs and ornate eaves serve not only as places of worship but as centers of communal life. During festivals like Chinese New Year or the Hungry Ghost Festival, temple courtyards transform into bustling food hubs. Temporary stalls appear overnight, offering pineapple tarts, yusheng (a raw fish salad tossed for prosperity), and steamed buns. The open layout of these courtyards—designed for gathering and ritual—naturally accommodates large crowds and food service. The architecture, rooted in tradition, becomes a stage for culinary expression.

Among the Kadazan-Dusun, indigenous architecture plays an equally vital role. Traditional homes, raised on stilts, are designed to protect against flooding and pests while allowing air to circulate beneath the floor. This elevated structure has shaped cooking practices—open-air kitchens are common, with firewood stoves placed under wide overhangs. The result is food that carries the subtle flavor of smoke and the freshness of open-air preparation. Dishes like pansoh, chicken or fish cooked in bamboo with herbs, are best prepared this way, the bamboo sealed and roasted over an open flame. The architectural choice of building high off the ground thus directly influences the taste and technique of the cuisine. Even in modern homes, this legacy persists—many families maintain outdoor cooking areas, preserving the connection between space and flavor.

The Malay community’s architectural contributions are equally significant. Traditional Malay houses, with their steeply pitched roofs and wide verandas, are designed for ventilation and social interaction. The open-plan layout encourages family meals and communal dining, reinforcing the cultural importance of food as a unifying force. In neighborhoods where these homes still stand, it’s common to see neighbors sharing meals on the porch, passing dishes across low tables. The architecture fosters generosity, intimacy, and ease—qualities that define Malay hospitality. Even in newer developments, these principles are echoed in the design of community centers and public spaces, where food is often at the center of gatherings. The built environment, therefore, does more than shelter food—it shapes the way it is experienced.

Modern Bites: Contemporary Spaces Reinventing Tradition

As Kota Kinabalu grows, so too does its architectural landscape. Modern developments like Suria Sabah mall and newly built civic centers reflect a city embracing the future without forgetting its roots. These spaces, with their glass facades, open atriums, and energy-efficient designs, offer a new kind of backdrop for traditional food. Inside Suria Sabah, for example, a locally run food hall brings together vendors from across the city, each serving regional specialties in a clean, well-lit environment. The design prioritizes comfort and accessibility—ample seating, climate control, and clear signage—making it appealing to families and older visitors who may find street stalls less accommodating. Yet, the food remains authentic. A stall selling laksa Sabah, a rich noodle soup with a broth made from dried seafood and spices, operates here just as it does on the sidewalk, the vendor using the same recipe passed down through decades.

Beyond shopping malls, a quieter revolution is taking place in repurposed buildings. Former offices, warehouses, and even a renovated civic building have been transformed into cafés and eateries that blend heritage charm with contemporary design. One such space, tucked away in a quieter neighborhood, features exposed brick walls, reclaimed wood tables, and large windows that flood the interior with natural light. Here, young entrepreneurs serve modern takes on traditional dishes—think grilled ikan bakar with a tamarind glaze, or pandan-flavored kuih served in biodegradable packaging. The architecture supports sustainability, both in materials and in ethos. Solar panels, rainwater harvesting systems, and natural ventilation reduce environmental impact, aligning with a growing awareness of ecological responsibility.

What makes these modern spaces successful is their balance. They do not erase tradition; they reframe it. The open layouts invite social dining, echoing the communal spirit of street food culture. The use of local materials—bamboo, rattan, and recycled timber—pays homage to Borneo’s natural resources. Even the lighting design, with warm-toned LEDs and pendant lamps made from woven fibers, creates an atmosphere that feels both contemporary and rooted. These spaces prove that innovation and authenticity are not opposites—they can coexist, each enhancing the other. For travelers, they offer a comfortable entry point into the city’s food culture, especially for those unfamiliar with street eating. But they also serve locals, providing a space where tradition is honored in a modern context.

The Night Market Experience: Light, Structure, and Street Energy

No visit to Kota Kinabalu is complete without experiencing its night markets, where food, light, and architecture converge in a vibrant spectacle. Along the waterfront and in neighborhood squares, temporary structures rise each evening, transforming ordinary spaces into culinary destinations. These markets are not permanent buildings but carefully orchestrated arrangements of modular stalls, metal awnings, and folding tables. Yet, their design is far from haphazard. The layout is optimized for flow—wide aisles prevent congestion, while designated zones for grilling, steaming, and seating ensure safety and efficiency. Overhead, string lights crisscross the space, casting a golden glow that enhances the warmth of the food and the faces of those enjoying it. The lighting does more than illuminate; it creates mood, turning a simple meal into a shared celebration.

The materials used in these temporary structures are chosen for durability and function. Metal frames withstand the coastal humidity, while waterproof canopies protect against sudden tropical showers. Stalls are often painted in bright colors—crimson, turquoise, saffron—adding to the visual energy of the scene. Each vendor personalizes their space with banners, lanterns, and hand-painted signs, turning their stall into a mini-identity. The result is a patchwork of individuality within a cohesive whole, much like the city itself. The design allows for flexibility—vendors can adjust their setup based on crowd size or weather—while maintaining a sense of order. This adaptability is key to the night market’s success, enabling it to thrive in a dynamic urban environment.

But beyond structure and light, it’s the human element that defines the night market. Families gather around shared tables, children chase each other between stalls, and elderly couples sip sweet teh tarik while watching the world go by. The architecture, though temporary, facilitates connection. Benches are placed in clusters, encouraging conversation. Grilling stations are positioned downwind, minimizing smoke exposure. Waste bins are strategically located, promoting cleanliness without disrupting the flow. These small but thoughtful design choices reflect a deep understanding of human behavior. The night market is not just a place to eat—it’s a social institution, a nightly ritual that brings the city together. In this space, food is not consumed in isolation; it is shared, celebrated, and remembered.

Beyond the Plate: Why Built Environment Matters in Food Travel

Too often, food travel is reduced to a checklist of must-try dishes. But in Kota Kinabalu, the experience is richer when you consider not just what you eat, but where you eat it. The built environment is not a passive backdrop; it is an active participant in the meal. A breeze flowing through a courtyard makes a plate of spicy sambal less intense. The echo of a wok in a tiled market amplifies the sensory drama of cooking. The sight of colorful mosaic tiles on a shophouse wall enhances the joy of sipping a cold drink after a long walk. These elements—often overlooked—shape the way we perceive flavor, texture, and atmosphere. Research in environmental psychology supports this: surroundings influence mood, which in turn affects taste perception. A meal enjoyed in a well-designed, comfortable space is often remembered as more satisfying, even if the food is identical to one eaten elsewhere.

This connection is part of a broader shift in travel preferences. Today’s travelers, especially those between 30 and 55, seek authenticity not just in food, but in context. They want to understand how a dish came to be, who makes it, and where it fits in the community. Architecture provides clues. A weathered shophouse tells a story of resilience. A temple courtyard reveals the role of food in ritual. A modern food hall reflects a city’s commitment to progress and inclusion. By paying attention to these details, travelers gain a deeper appreciation of culture. They move beyond consumption to connection. This is not tourism as spectacle, but as engagement. It requires slowing down, observing, and listening—not just to people, but to places.

Kota Kinabalu exemplifies this philosophy. Its architecture, whether centuries-old or newly built, is never just about aesthetics. It is about function, identity, and community. And when food enters the equation, the relationship becomes even more profound. A dish is not just a product of ingredients and technique; it is shaped by the space in which it is made and served. The height of a ceiling, the material of a countertop, the direction of the wind—all play a role. Recognizing this transforms the way we travel. It invites us to see cities not as collections of landmarks, but as living systems where culture, environment, and daily life are intertwined. In Kota Kinabalu, every meal is a conversation between past and present, between people and place.

Traveler’s Guide: How to See (and Taste) Kota Kinabalu Like a Local

To truly experience Kota Kinabalu, start early. The morning market is at its liveliest between 7:00 and 9:00 a.m., when vendors are restocking and the air is still cool. Bring a reusable bag and a small notebook to jot down names of dishes or ingredients you’d like to try later. Wear comfortable shoes—many of the best food spots are found by walking, not driving. Begin with Gaya Street, where the historic shophouses line both sides of the road. Look up as you walk; notice the architectural details above shop level, where decorative cornices and ironwork often go unnoticed. Stop for breakfast at a local stall serving roti bakar with kaya and coffee—simple, satisfying, and deeply traditional.

By midday, seek shade and hydration. A visit to a modern café in a repurposed building offers a chance to rest while still engaging with the city’s evolving food culture. Order a fresh coconut or a glass of lime juice, and take time to appreciate the interior design—how natural materials, lighting, and spatial layout contribute to the experience. In the late afternoon, head to the waterfront promenade. Walk the length of the boardwalk, observing how the architecture interacts with the sea and sky. As dusk approaches, the night market begins to set up. Arrive early to secure a good seat, and be respectful when photographing vendors—ask permission when possible, and avoid using flash. Try small portions of several dishes: grilled squid, steamed buns, and a bowl of noodle soup. Share a table with others if space is tight; it’s often the best way to start a conversation.

For those interested in deeper exploration, consider a self-guided walking tour focused on architectural details. Look for patterns: the use of color, the placement of windows, the way buildings relate to the street. Notice how older structures are adapted for modern use, and how new buildings incorporate traditional elements. Carry a small camera or use your phone to document details—a carved door, a tiled floor, a weathered sign. These images will help you remember not just what you ate, but where you were. Above all, move at a slow pace. Let the city reveal itself gradually. Eat with curiosity, observe with care, and allow the harmony of food and architecture to deepen your understanding of Kota Kinabalu.

A City Best Savored with All Senses

Kota Kinabalu’s true essence lies in the harmony between what you eat and what surrounds you. It is a city where every meal is framed by history, culture, and design. The flavor of a dish is enhanced by the breeze through a colonial arcade, the glow of lanterns in a night market, the echo of footsteps in a heritage market. To travel here is not just to taste, but to see, hear, and feel. The architecture is not decoration—it is context, a silent narrator of the city’s story. And in that story, food is not an add-on, but a central character.

For travelers, especially those seeking meaningful, authentic experiences, Kota Kinabalu offers a powerful lesson: that the best journeys engage all the senses. They invite us to slow down, to notice details, to appreciate the invisible threads that connect people, places, and plates. The next time you travel, look beyond the menu. Study the walls, the windows, the way the light falls. Let the built environment guide your palate. Because the true taste of a place is built long before the first bite—it is shaped by generations, by geography, and by the quiet beauty of everyday spaces. In Kota Kinabalu, that truth is served with every meal.