You Gotta See What This Hidden Corner of Senegal’s Selling

When I first stepped into Ziguinchor’s bustling markets, I wasn’t just shopping—I was diving into a vibrant story of culture, craft, and color. This quiet region of Senegal pulses with authenticity, far from tourist traps. From handwoven baskets to bold fabrics and local art, every purchase feels meaningful. If you're looking to take home more than souvenirs—if you want connection—Ziguinchor’s shopping scene delivers. Let me show you where to go, what to buy, and how to do it right.

Why Ziguinchor Stands Out in West African Travel

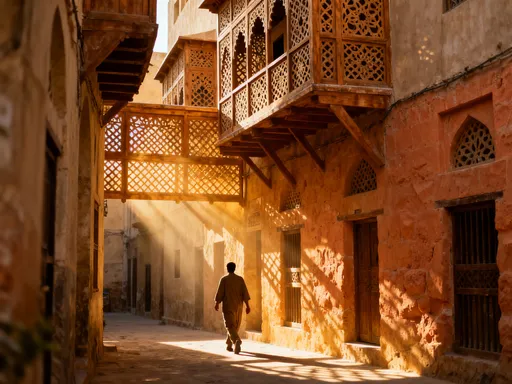

Situated in the southern part of Senegal, Ziguinchor is the cultural and economic heart of the Casamance region—a lush, green contrast to the drier north. Known for its fertile lands, winding rivers, and tropical forests, Casamance offers a landscape unlike any other in the country. But what truly sets Ziguinchor apart is its cultural distinctiveness. The Diola people, who make up a significant portion of the population, have preserved traditions, spiritual practices, and craftsmanship that reflect a deep connection to the land and ancestral knowledge.

Unlike the more touristed areas such as Dakar or Saint-Louis, Ziguinchor has remained relatively untouched by mass tourism. This isn't due to lack of beauty or significance—it's because access has historically been more complex, requiring either a domestic flight or a long overland journey. Yet this isolation has become a strength, allowing local customs and artisanal practices to flourish without commercial dilution. Travelers who make the journey are rewarded not with polished performances for visitors, but with genuine daily life unfolding in full color and rhythm.

The city itself sits along the Casamance River, where fishing boats glide at dawn and women wash clothes along the banks using age-old methods. Music drifts from open-air cafes—soft kora melodies and traditional drumming that speak of community and continuity. In this environment, shopping is not a detached transaction but an immersive experience, woven into the fabric of social life. Whether you're browsing for textiles, tasting local produce, or watching a potter shape clay by hand, you're participating in centuries-old traditions that value craftsmanship, sustainability, and human connection.

For women travelers, especially those between 30 and 55 who seek meaningful travel experiences, Ziguinchor offers something rare: authenticity without pretense. There’s no pressure to perform or consume. Instead, there’s space to observe, engage, and learn. The pace is slower, the smiles warmer, and the interactions more personal. This is not a place to check off landmarks, but to absorb a way of life that honors nature, heritage, and community.

The Heartbeat of Commerce: Marché Central de Ziguinchor

If Ziguinchor has a soul, it beats loudest in the Marché Central. This sprawling marketplace is not just a place to buy goods—it’s where life happens. From sunrise, the market buzzes with energy as vendors arrange pyramids of mangoes, pineapples, and papayas. Spices fill the air with warm, earthy scents: turmeric, ginger, and the distinctive aroma of dried thiof fish. Women in brightly colored boubous move gracefully between stalls, balancing baskets on their heads while negotiating prices with practiced ease.

The market is organized into distinct sections, each dedicated to a category of goods. The textile zone is a feast for the eyes, with bolts of wax-print fabric in every imaginable pattern—geometric designs, floral motifs, and symbolic messages woven into the dyes. These fabrics are more than fashion; they communicate identity, status, and even proverbs. Nearby, artisans display hand-carved wooden bowls, raffia baskets, and ceramic cookware used in everyday Senegalese kitchens. The produce section overflows with seasonal fruits and vegetables, many grown in nearby villages using organic methods passed down through generations.

For visitors, the key to enjoying the market is approaching it with respect and curiosity. The best time to visit is early in the morning, between 8 and 10 a.m., when the heat is still bearable and the selection is freshest. It’s also when vendors are most open to conversation. While French is widely spoken, a simple “Bonjour, ça va?” goes a long way in building rapport. Carrying small bills is essential, as change can be hard to come by, and bringing a reusable tote bag helps reduce plastic use while making transport easier.

One of the most striking aspects of the market is the absence of aggressive sales tactics. Vendors are welcoming but not pushy. They understand that genuine interest leads to better exchanges than forced transactions. If you take the time to ask about a fabric’s origin or the use of a particular cooking pot, you’ll often be rewarded with a smile, a story, or even an invitation to see how it’s made. This is not retail as usual—it’s relational commerce, where every interaction carries weight and meaning.

Beyond the Market: Hidden Workshops and Artisan Encounters

While the Marché Central offers a vibrant overview of local crafts, the real magic happens behind the scenes—in small workshops tucked into quiet neighborhoods or rural villages outside the city. These are the places where artisans spend hours perfecting their skills, often within family-run operations that have been passed down for generations. Visiting these spaces allows travelers to witness the creation process and connect directly with the makers.

One such destination is a cooperative in the village of Nguidjilone, about 30 minutes from Ziguinchor, where women produce hand-dyed textiles using natural pigments from roots, leaves, and bark. The process is slow and meticulous: cotton fabric is first soaked in a tannin-rich solution made from mangrove bark, then hand-painted with intricate patterns using a cassava-based paste. After drying, the cloth is dyed in fermented mud—a technique similar to Malian bogolan but with its own Diola variations. The result is a rich, earth-toned textile that tells a story in every stitch.

Another notable stop is a woodworking atelier in Boutoupa, where male artisans carve ceremonial masks, stools, and figurines from local woods like iroko and ebony. Each piece is imbued with symbolic meaning—masks used in Diola initiation rites, stools representing ancestral lineage, or animal carvings reflecting spiritual beliefs. Unlike mass-produced “ethnic” decor sold in tourist shops, these items are made for cultural use first and adapted for sale second, ensuring authenticity and respect for tradition.

Reaching these workshops often requires the help of a local guide or community liaison. Many cooperatives welcome visitors by appointment, especially when arranged through eco-tourism agencies or women’s collectives in Ziguinchor. These visits are not just sightseeing—they’re educational exchanges. Artisans appreciate questions about their techniques and are often eager to share the meanings behind their work. In return, travelers gain a deeper understanding of Casamance’s cultural fabric and contribute directly to sustainable livelihoods.

What to Buy (And What to Skip)

Shopping in Ziguinchor offers a rare opportunity to bring home items that are both beautiful and meaningful. But with so many options, it’s important to know what to seek—and what to avoid. The most valuable purchases are those made directly from artisans or cooperatives, where the money supports local families and preserves traditional skills.

Among the top authentic items to look for is handwoven raffia basketry. Crafted by Diola women using techniques unchanged for centuries, these baskets come in various sizes and patterns, each with a specific purpose—some for carrying goods, others for ceremonial use. They are lightweight, durable, and make elegant decorative pieces back home. Equally worthwhile is traditionally made shea butter, produced by women’s groups using slow-roasted nuts and cold-press methods. Unlike commercial versions, this shea butter retains its natural healing properties and rich scent, making it a nourishing addition to any skincare routine.

Textiles are another highlight. Look for hand-stitched fabrics inspired by regional weaving traditions, often blending Diola motifs with influences from neighboring West African cultures. These are not mass-produced imitations but unique pieces that reflect the maker’s artistry. Ceramic cookware, such as wide-mouthed clay pots used for slow-cooking stews, is also a functional and symbolic purchase. These pots are made without a wheel, shaped entirely by hand, and fired in open pits—methods that have sustained communities for generations.

On the other hand, travelers should be cautious of items that appear too perfect or too cheap. Mass-produced “tribal” masks made in factories outside Africa, synthetic fabrics printed to mimic hand-dyeing, and jewelry stamped with generic “African art” labels lack authenticity and often exploit cultural symbols. These items may be convenient, but they contribute to the erosion of genuine craftsmanship. When in doubt, ask about the item’s origin. A true artisan will proudly explain how and where it was made.

The Art of Bargaining: How to Shop with Respect

Bargaining is a common practice in West African markets, and it’s expected in Ziguinchor. However, it’s crucial to approach it not as a competition, but as a conversation. The goal is not to get the lowest possible price at the vendor’s expense, but to reach a fair agreement that respects both parties.

In the Marché Central, prices are often marked up slightly with the expectation of negotiation. A polite way to begin is to ask, “C’est combien?” (How much?) and then respond with a counteroffer that’s reasonable—typically 20 to 30 percent below the initial quote. Smiling, maintaining eye contact, and speaking slowly in French or attempting a few words in Diola can help build trust. Phrases like “C’est un beau travail” (That’s beautiful work) or “Je veux aider” (I want to help) signal appreciation and goodwill.

It’s also important to recognize that many vendors are supporting families, paying for children’s education, or reinvesting in their craft. A price that seems high by Western standards may be modest in local terms. Rather than haggling aggressively, consider the value of what you’re receiving—not just the object, but the story, skill, and time behind it. Sometimes, paying the full price is the most respectful choice, especially when buying from a cooperative or elderly artisan.

Children often assist their parents at stalls, and it’s common to see young girls folding fabrics or boys carrying goods. Treat them with kindness and avoid giving money or candy directly, as this can encourage them to prioritize tourism over school. Instead, acknowledge their role with a nod or a gentle compliment. These small gestures foster mutual respect and contribute to a positive cultural exchange.

Supporting Sustainable Tourism Through Shopping

Every purchase in Ziguinchor has the potential to make a lasting impact. When travelers buy directly from artisans, they help sustain rural economies that rely on traditional crafts for income. This support is especially vital for women, who often lead cooperatives and use their earnings to fund education, healthcare, and community development.

Several initiatives in the region exemplify this model. The Association des Artisanes de Ziguinchor, for instance, trains women in textile production and provides them with a collective sales platform. Profits are reinvested into vocational programs and microloans for new entrepreneurs. Similarly, the Casamance Shea Collective works with over 200 women across 15 villages, ensuring fair wages and eco-friendly harvesting practices. By choosing to buy from such groups, travelers become part of a larger movement toward ethical and sustainable tourism.

Environmental stewardship is also a key component. Many artisans use renewable materials—raffia, clay, natural dyes—and traditional methods that minimize waste. Unlike industrial production, their work is low-impact and deeply connected to the local ecosystem. Supporting these practices helps protect Casamance’s fragile environment while preserving cultural heritage.

Travelers can deepen their impact by asking questions: Who made this? Where did the materials come from? How is the income used? These conversations not only build trust but also educate consumers about the true cost and value of craftsmanship. In doing so, shopping becomes an act of solidarity—a way to honor the people behind the products and ensure their traditions endure for future generations.

Bringing It All Home: Packing, Customs, and Lasting Value

After a rewarding shopping experience, the next step is bringing your treasures home safely. Many of the items purchased in Ziguinchor—such as pottery, wooden carvings, and woven baskets—are durable but can be bulky or fragile. Wrap ceramics in soft cloth or bubble wrap, and place them in the center of your suitcase, surrounded by clothing for cushioning. Raffia bags can be rolled or folded, while textiles should be folded neatly to prevent creasing.

When it comes to customs regulations, most handmade goods are allowed into other countries for personal use. However, items made from plant-based materials—like raffia or certain wooden carvings—may require declaration, especially if traveling to regions with strict agricultural import rules, such as the United States or the European Union. It’s wise to keep receipts or certificates from cooperatives, which can serve as proof of ethical sourcing and artisanal origin.

Once home, these items become more than decorations—they become conversation pieces. A raffia basket on the wall reminds you of the woman who wove it under a mango tree. A clay pot used for soup connects you to generations of Diola cooks. A hand-dyed textile draped over a chair carries the scent of earth and fire. These objects keep the spirit of Casamance alive in your daily life, inviting questions and stories from family and friends.

More importantly, they serve as quiet reminders of the power of thoughtful travel. In a world where mass tourism often erodes local cultures, choosing to engage deeply, buy ethically, and listen carefully is a form of resistance. It affirms that travel can be transformative not just for the visitor, but for the communities we visit.

Ziguinchor teaches us that shopping can be sacred. It’s not about acquiring more, but about connecting deeper. It’s about honoring the hands that create, the land that sustains, and the stories that endure. When you return home with a basket, a cloth, or a pot, you’re not just carrying souvenirs—you’re carrying forward a legacy of care, craft, and cultural pride. And that’s a journey worth taking.